Are There Bad Questions And Good Questions?

The more I started to look at questions and how essential they are to fostering creativity and innovation, the more I realized that there are bad questions and there are good questions. And within those good questions, some just aren’t relevant to the process of ideation. The key is to develop the a

The more I started to look at questions and how essential they are to fostering creativity and innovation, the more I realized that there are bad questions and there are good questions. And within those good questions, some just aren’t relevant to the process of ideation. The key is to develop the ability to separate the good, useful questions from the bad ones.

I’m always on the search for questions that challenge thinking – that reveal breakthrough innovations.

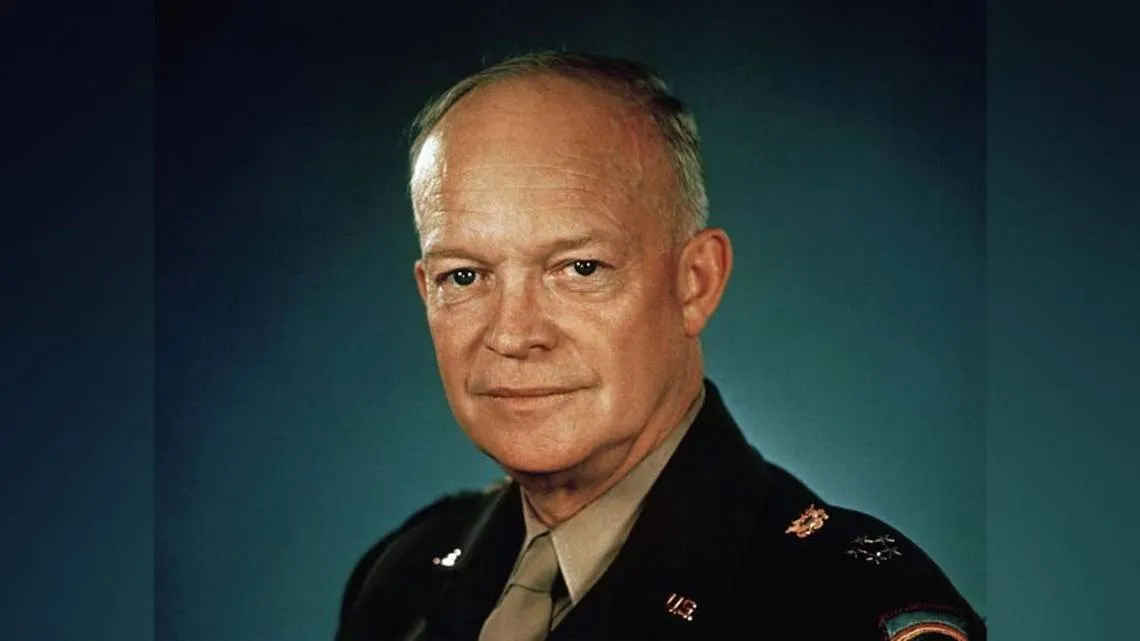

Phil McKinney

Here’s a quick guide:

Bad Questions: Tag Questions

During my search, I realized that some of the most important questions to avoid are ones that don’t really ask for a response at all. For example, tag questions. Tag questions are statements that appear to be questions, but don’t allow for any kind of answer except agreement. A tag question is really a declarative statement turned into a question, and used to get validation for the speaker’s “answer.” Family members, authority figures, or executives who want to appear to care about the opinion of another person, but really want their instructions carried out without discussion, often favor tag questions. A tag question can show that the speaker is either overly confident of his or her beliefs, or so insecure that he has to bully others into agreeing with him. Either way, his phrasing of the question shows that he is not willing to consider an alternative point of view. You’re not actually being asked for an opinion, simply for a confirmation that you agree with them. When lawyers use tag questions in a legal setting, they are sometimes referred to as leading the witness, the questions being posed in such a way as to guide the person in a desired direction, and that is how you should think of a tag question as well.

That presentation was fantastic, wasn’t it?

The new brochure will be based on the last version, won’t it?

Tag questions can be incredibly damaging both to an individual and to an organization because they shut down the creative process. Say you’ve been tasked to come up with a new product but your boss asks you to verify that “the new concepts that you are coming up with aren’t going to be too different from the old ones, right?” By asking this question she has taken away any power from your team to go out and do something really new. The fundamental point of asking a question is to get information, input, or ideas. Any question that restricts people from feeling free to honestly answer it is offensive; it reduces the quality of information you’re going to get and makes the person being questioned feel that they are being dismissed.

Typically a person who uses tag questions is a manager who believes that his role is to be directive. However, by doing so he misses out on the potential power of a team. Look at the way you communicate with your coworkers; if you find yourself asking tag questions ask yourself why. Do you doubt their ability to come up with their own answers, or do you already have an answer in mind that you would like them to validate? If you are simply looking to get validation for what you already want or believe, this runs counter to every philosophy about generating new and innovative ideas. When I’m working with a team, I’ll always use a series of questions to see what they come up with, even when I already have an idea in my mind of what the answer may be. Even if I give them that answer, it’s always presteamented as a challenge for them to come up with something better.

To be clear, a tag questions are bad questions.

Good Questions: Factual vs. Investigative

After more searching and studying, I came up with two basic categories of good questions: factual and investigative. So, what are the differences between them? The objective of a factual question is to get information: “Do you want coffee or tea?” “How many units did we sell last week?” “Is there gas in the car?” You may not know the immediate answer to a factual question, but you know how to find it. There is no real discovery required beyond expressing your opinion, making a call, or looking at the gas gauge. Factual questions serve an important purpose in allowing us to communicate with one another and exchange information. They are limited in their ability to do anything more nuanced than gather information.

An investigative question, on the other hand, cannot be answered with a yes or a no and is much more useful for our purposes. By definition, it is a divergent question, meaning that there is more than one correct answer (unlike factual questions). It cannot be answered with one phone call or a quick check at some stats or figures, and it forces us to investigate all of the possibilities.

The Socratic Method

So how do you generate some good investigative questions? One of my starting points is the Socratic Method. Socratic questions are, in their simplest definition, questions that challenge you to justify your beliefs about a subject, often over a series of questions, rather than responding with an answer that you’ve been taught is “correct.” A well-phrased series of Socratic questions challenges you to think about why you believe your “answer” to be correct, and to supply some sort of evidence to back up your beliefs. At the same time, a Socratic set of questions doesn’t assume you are right or wrong.

When using this method, Socrates would lead his listener to a deeper understanding of his own beliefs and how and why he justified them. When a student attempted to fall back on a belief prefaced by “I’ve heard it said that such and such is true,” Socrates would gently push further, asking the student what he himself actually thought, until the student finally got to the heart of what he thought and believed. Socrates would also find contradictions in a student’s expressed belief, and ask him questions that forced him to consider these contradictions. Ultimately Socrates’s goal was to help the student unveil his own thoughts, his own beliefs, and see them clearly for the first time, because it was only by finally articulating one’s own thoughts and bringing them into “open air” that the student could fully understand the depths of his own knowledge.

Socrates believed that knowledge was possible, but believed that the first step toward knowledge was a recognition of one’s ignorance. It’s the same in the idea-generation process; the first step to freeing yourself to find innovations is to recognize that the knowledge you currently have is insufficient, and that you need to go out and discover new information that will lead to new products or concepts.

My interest in the Socratic Method, and the glaring gap I found between Socrates’s method of teaching with questions and the way innovation and ideation is “taught” today, started me down the path of searching for specific questions that would challenge others to find opportunities for new ideas—questions I now call Killer Questions. It took me a while to determine them, but in the end I hit upon the old engineering standby: Find something that works, and figure out why.

Phil McKinney Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.