Building and Testing The Killer Questions

I started collecting the Killer Questions when I was in my short-lived “retirement” early in 2001. As I relaxed in the Virginian countryside, my mind started to flash back to various experiences I’d had during my working life. Over the course of the preceding twenty years I’d seen dozens of highly i

I started collecting the Killer Questions when I was in my short-lived “retirement” early in 2001. As I relaxed in the Virginian countryside, my mind started to flash back to various experiences I’d had during my working life. Over the course of the preceding twenty years I’d seen dozens of highly innovative products and ideas come to market. I started to ask myself a broad range of investigative questions about how and why successful products work. The most important issue seemed to be that of understanding the thought process that led to these discoveries.

One memory from my old career jumped into my head. In late 1994 I was sitting in a limo in a traffic jam in Bangkok. We’d been in traffic for half an hour, and I had only twenty-eight minutes until a critical meeting started. The limo was cooled to American standards, and the German steel and glass kept the chaotic noise and rush of people outside the doors. At twenty-three minutes I started to feel a little anxious; the car wasn’t moving, but the clock was. I tapped the driver on the shoulder and tried to communicate my sense of urgency, but he wasn’t interested. He knew we weren’t going anywhere soon, and I wasn’t doing myself any favors by worrying about it. At eighteen minutes to go I jumped out of the car and hailed a motorcycle taxi.

Killer Questions challenge you to think differently. A great Killer Question will surprise you with its answer.

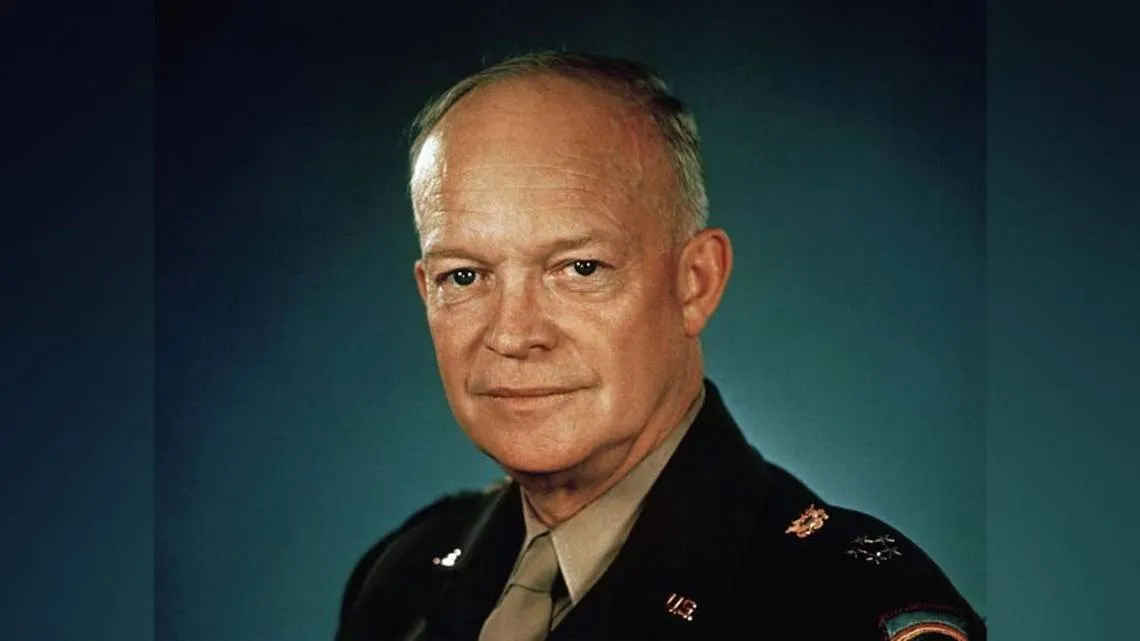

Phil McKinney

Thai motorbike taxis are 150ccs of terror. I’ve ridden motorcycles before, but I can honestly say I’ve never felt as close to disaster as I did then, riding pillion on a tiny Chinese motorcycle, going flat-out through the sweltering heat with my briefcase clutched to my chest. As we swerved through the tuk-tuks, pedestrians, and stalled cars I found myself thinking about the difference between the super-cheap motorcycles that swamp the streets of Southeast Asia and the ultraluxe bikes manufactured by companies like Harley-Davidson. How had something that started as cheap and efficient transportation for the American working man evolved into a big-ticket luxury item? Who was the first person who thought, Can we take our mass-produced product and customize it? What if we stop trying to make our product cheaper, and go the other way? What happens if we double, maybe triple, the price and make this a luxury item instead?

I thought about the contrast between a very mainstream product (the inexpensive motorcycle) and the one that had breakout success (Harley-Davidson). Could I reverse-engineer this evolution of a product, and figure out the question that could lead someone to come up with that idea? And if I could reverse the thought process that led to innovative products and find the questions that might have generated these ideas, would those same questions lead to new discoveries and new products in the future? With these questions in mind, I wrote down this first question — Who is passionate about your product or something it relates to? Why or why not?—on a blank white index card and resolved to keep doing so each time I came across other questions that seemed to spark especially good ideas.

The Killer Questions

As the months passed, these cards started to multiply, so I decided to put together a card deck that I kept in a big binder clip. Before each innovation workshop I’d flip quickly through the set and pull out a few questions to ask the participants. I constantly tested the questions in workshops to see which questions would generate the best ideas. I kept the ones that worked and tossed the ones that didn’t. Sometimes I realized that a question had the potential to spark a good idea, but I had worded it poorly, so I experimented with the question by adjusting the language.

After a year or so the walls in my home office were filled with Killer Questions. They were scrawled on index cards and stuffed in shoeboxes or pinned up on the wall. The sheer volume was driving my wife crazy. That’s when I realized I needed to formalize the system, strip it down to the most effective questions, and develop a way to organize and use them. You’ll learn more as we go through the book, but for now know that the Questions are divided into three categories:

- Who your customer is

- What you sell them

- How your organization operates.

Each category has roughly twenty questions to date, and more are constantly being tested and added to the card deck.

So, is the list static? No. The key to the value of the Killer Questions is that new ones are continuously being discovered. Sometimes I get questions sent to me by the listeners to my podcast. Other times I come up with new ones in support of an upcoming workshop, or they come to me when I’m reading a story in the Sunday paper.

Testing The Killer Questions

The questions that I keep are ones that trigger something for someone. Did a new question cause a listener or reader to see something differently about their product, customer, or organization? Did it spark a broader examination of how they were doing something, and why?

One of my favorite killer questions is one of the simplest: “What do my potential customers not like about the buying experience?” This is a classic Killer Question; on first glance it seems obvious, but once people start to think about it they realize they’ve never actually asked that of themselves or their business. In fact, the overwhelming majority of organizations do not measure or track what their potential customers dislike about their buying experience, instead choosing to focus on issues with the product or support. In reality this question is almost impossible to measure. Think about it. How would you find a potential customer who had such a bad buying experience that they didn’t buy your product? Digging into what the potential customer actively dislikes about buying a product can be a gold mine, especially when your competitors aren’t making that investigation.

The only way to capture this information is to be right there observing your customers in action as they select or reject your product. You can’t e-mail or follow up with them, because you don’t know who they are; they didn’t buy your product. You have to catch them in the moment and ask them right then and there. The question gives you a broad area to look at: It could be a brand, sales, marketing or merchandising issue. The point of a Killer Question is to challenge you to look at things in a new and different way. A really good Killer Question will leave you surprised by the answer.