The Power of Questions And How To Use It!

I’ve been fascinated by the power of questions, either good or bad, for my entire professional life. The more I thought about them, the more I began to notice how people used them. I started to see how some people had the innate ability to formulate and pose questions that propelled others to make i

I’ve been fascinated by the power of questions, either good or bad, for my entire professional life. The more I thought about them, the more I began to notice how people used them. I started to see how some people had the innate ability to formulate and pose questions that propelled others to make investigations and discoveries of their own, and some people had the less-desirable ability to shut their listeners down with bad questions, poorly asked.

I believe that a good question is one that causes people to really think before they answer it, and one that reveals answers that had previously eluded them. I began to think more about how an individual could learn to ask good questions and avoid the pitfalls of asking bad questions. I also wondered whether a poor questioning technique could become a crutch, something that allows you to believe you are accomplishing something positive, when in fact you are doing the opposite.

As I listened to my children ask challenging questions of each other I realized I had taught them a profound skill. By passing on a love of the power of questions I’d shared my belief in the importance of getting out there and proactively making our own discoveries about the world. My children weren’t afraid or ashamed of not knowing an answer, instead they were invigorated by the process of finding it. I compared this attitude to the converse one that I’d seen throughout my career, namely employees who felt compelled to agree with their superiors or believed that saying “I don’t know” would adversely affect their career. These men and women would have benefited greatly from simply being empowered to admit that they didn’t know, to ask good questions, and to seek out the relevant answers. My hope is to develop a similar passion for discovery in those who focus on a larger, business-oriented audience.

Good question cause people to find answers that previously eluded them.

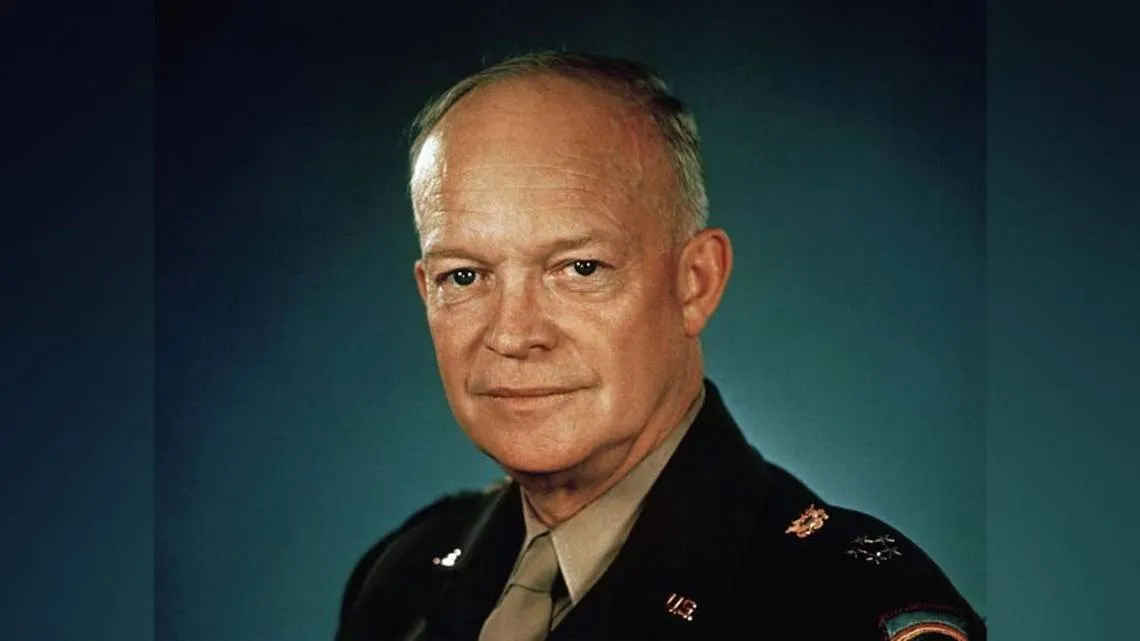

Phil McKinney

How The Power of Questions Work

If you are going to start thinking about the power of questions, it is helpful to understand what a fundamental shift it was for humans to learn how to ask them. According to primatologists, the great apes can understand and answer simple questions. However, unlike humans, a great ape has never proven that it can ask questions. Nor has any other creature, at least in any way that’s recognizable to us. Your dog can make his desires known to you, but he can’t actually ask you to take him for a walk. All he can do is wag his tail and hope you figure out for yourself what he needs and wants. As a result, the ability to form a question might be the key cognitive transition that separates apes, and all other beings, from mankind. The desire to ask a question shows a higher level of thought, one that accepts that your own knowledge of a situation isn’t complete or perfect.

The natural world has some great examples of why this ability to think inquisitively is a critical survival skill. Have you ever seen an army ant mill? Army ants are an aggressive and nomadic variety of ant that moves constantly, unlike the ants that your kids display between glass at a science fair. Army ants have the innate drive to follow the ant in front of them, which makes sense if you are a member of a colony on the move. This instinct allows them to move cohesively and maintain their colony, but it is also their greatest flaw. Every so often the head of an army-ant column runs into its tail. The ant who was leading the way sees an ant in front of it and the genetic programming kicks in; he goes from leader to follower, and the column of ants turns into a circle, or mill. The ants have no ability to break free from the circle, and they keep walking until they die. The only thing that can save them is if there is a “broken” ant in the mill, one whose programming to “follow the ant in front” is missing or flawed in some way. This ant will step out of formation, the ant behind him follows, the mill is broken, and the colony saved.

Recent research validates this idea that “brokenness” is a key element to a questioning and creative spirit. Scientists have started to prove what most people in the tech or other creative spheres already know: If you want to be innovative, it helps to be a little bit “different.” True genius seems to come when extremely intelligent people have high levels of cognitive disinhibition. In other words, they are naturally smart people who don’t filter the information they absorb and have the mental agility to process and use this information in an organized way.

Now, I want to be clear that I am using terms like “brokenness” or “different” in the most positive way; after all, the core of this book is learning how to use the power of questions to think differently—to cause your own version of cognitive disinhibition—even if it’s not your automatic instinct. I believe that anyone can develop and harness this power through the use of provocative questioning and discovery.