Not Relying on Specialized Knowledge

What do you think your core value or skill is? If you are resting on an assumption that a deep-rooted and highly specialized knowledge or skill is enough to get you by, you are mistaken. Back in 1995 or so, I noticed a sliver of an ad, one column wide and two lines deep, on […]

What do you think your core value or skill is? If you are resting on an assumption that a deep-rooted and highly specialized knowledge or skill is enough to get you by, you are mistaken.

Back in 1995 or so, I noticed a sliver of an ad, one column wide and two lines deep, on the front page of the New York Times. I don’t remember the exact wording, but the gist of it was “Amazon.com, a river of books.” I remember thinking that it must have been the cheapest ad the Times had ever sold on its cover, or perhaps it was an obscure prank. Instead, it was the opening shot in the war of old media versus new. I didn’t know of Jeff Bezos then, and I wondered what buying this ad space meant to this unknown entrepreneur. Was it a massive gamble and leap of faith? Was he risking his family’s financial future to buy that handful of words? Did he know where he was going and how he was going to get there?

I would love to go back in time and talk to Jeff about what he was thinking and feeling the moment he said, “OK, we’re doing this,” and placed that order for ad space. He and his partners were asking some pretty fundamental How Killer Questions about their customers’ willingness to completely change the way they bought books, and there was no guarantee they were going to get the response they wanted. Recognizing the importance of asking the questions you’d never previously considered, and being willing to follow through on what you learn by asking them, is what separates those who succeed from those who fail. It can be scary—but the risks of inertia are worse.

As I’ve said throughout this book, I believe that the nature of the global economy is changing. If you want to be perceived as a highly valuable asset, either to your company or to your customers, you have to understand who you are, what you do, and how to change the way you work and generate value as well.

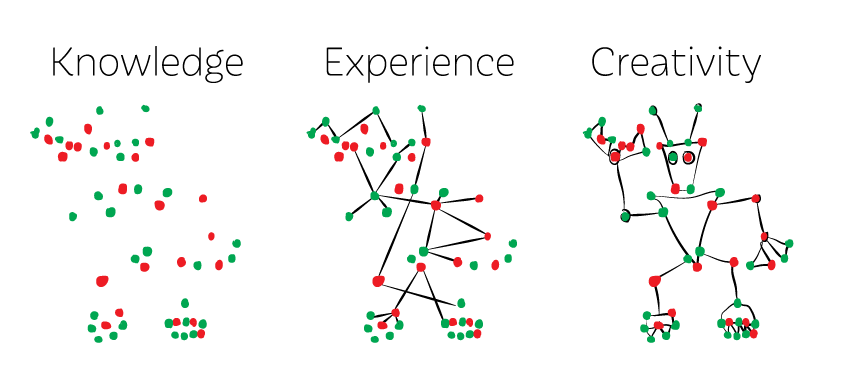

Knowledge used to be hard to acquire, and the difficulty of amassing it gave that knowledge—and the person who had it—value. A hundred years ago there were very few avenues for an individual to learn how to do something. You could either apprentice, be born into a family business, or be rich and talented enough to be accepted into one of the very few universities. Part of the value of knowledge was its scarcity. This has changed, and it is going to continue to change as the information economy segues into the creative economy. The most valuable asset in this new economy is not simply technical ability or having a deeper level of knowledge than others in your field; it’s your ability to apply your skills or knowledge in order to creatively come up with new ideas. It’s no longer about what you can do with your hands but what you can come up with using your brain. If you can address the innovation gap for whatever organization you’ve aligned yourself with and present innovations that don’t occur to your competitors, then you will have ensured the success of your organization.

It makes sense, really. The information that people have traditionally needed to succeed is becoming more and more accessible. When was the last time that Google was unable to answer a factual question for you? It’s probably been a while. Remember the scene from Catch Me If You Can, where the antihero crams for the bar exam in one night, and passes, without having attended law school? That scene, whether fact or fiction, is a good metaphor for how the nature of information as a product is continuing to change. He got his hands on the relevant books, applied himself to the task, and took the test. His knowledge may have been superficial, and he probably wouldn’t have lasted one day in court, but he was able to absorb enough information to pass the bar and get his foot in the door. And that was fifty years ago, long before the Internet age.

These days anybody with ambition, a sense of curiosity, and access to the web can learn what used to be restricted to the elite and the lucky. Now, the explosive growth of the university systems in India and China are creating a vast population of people who have the same specialized knowledge as you do. In many cases these armies of graduates are willing to sell that knowledge for substantially less than you are. As a result, your knowledge will no longer guarantee you a career. The people in charge no longer need you to have all the answers. They need you be able to ask the questions that lead to the right innovations.

By reading Beyond the Obvious, you are starting down the path to becoming a key player in the creative economy. But reading alone isn’t enough. You’ve learned the basics, but now you have to practice and apply these skills to real-world scenarios. And the more you apply them, the more you practice them, and the more you adapt them, the more you’ll find what works for you and the better you will be at asking the right questions. The key is to build up the confidence in yourself that you can take this leap, especially if you’ve never considered yourself a “creative” talent. Creativity is not a gift from God, and if you insist on seeing it that way, you’re simply giving yourself an excuse not to try.